England or Italy

Just days before my Father Lt. Ernest Anders Erickson received his orders for his Combat Flying assignment, as he mentioned, “I didn't have a clue where I would be stationed. England or Italy were the choices I figured, but it was not my place to choose, I just waited for my final orders to arrive.”

He knew it would not be the Pacific, so England or Italy were the only possibilities. Ernest had his sights on Italy with its warm climate, near the Mediterranean and Adriatic Seas. Growing up in the freezing winters of the landlocked State of North Dakota, his thoughts were of hot weather and swimming in the ocean. He’d heard plenty of reports from fliers coming back to the States after tours of duty beneath cold and cloudy English skies. England intrigued him, he'd heard a lot about the various Bomb Groups stationed throughout the countryside, that were involved with the daylight bombing of Nazi occupied Europe, but Italy had always held a passion in my father's eyes.

Ernest wanted to get going and England sounded fine. Not giving into intimidation by the immense losses of the bomber crews that were occurring in Europe in 1943, his crew felt ready to begin their combat flying. My father penned a letter home to his folks and little sister Dian from Langley, dated January 12, 1944. The letter was to inform his family of the possibilities of when he might head overseas.

4th Search Attack Squadron Langley, Virginia

January 12, 1944

Dear Dad, Mom and Dinny:

I got the pictures. They're real nice. Dian is a cute little kid. Too bad she has to squint because of the sun in that one shot. You said you hoped that I would be home next Christmas. If I'm not at home I will hopefully be in this country, as the Air Corps sends its men back after 25 raids. I've talked to several men that have completed their missions and are back here on base. That applies only to the English and German areas. In Africa and Italy, where the opposition isn't so stiff as in Germany, a fellow has to make 50 raids.

I'm leaving soon. This is no false alarm this time, as the Bombardier and three of the enlisted men are leaving in a couple days by boat. The rest of the crew will fly over later, so we'll more than likely meet-up in England or Italy. We're waiting for our ship to be ready, the maintenance crew are checking it over. I don't know if we'll fly the Northern or Southern route across the Atlantic. This clipping will tell you why I'm here.

It's quite a deal, and our crew will be a lead ship.

There's no chance of getting up to see Angie and Flo again as we have to stand three rolls calls on Sunday at 0800, one o'clock and 5 o'clock. Guess they do not like to see us get too far away. We're free to leave the post and stay out all night, just so we come back in time to fly. But that's not long enough to really go anywhere.

That's quite the hat that Dad has on. Looks like a Russian hat, or one of those that the Turks wear. I see in the picture that the ground is free of snow. Good deal! It makes it easier to get around. Quentin Rudd is overseas I hear. He apparently went to England and is flying off one of those bases in the countryside of England. I have a six hour over the ocean mission tomorrow morning. Better get to bed.

Love, Ernie

Ernest followed up with another letter, dated January 18th, 1944 from Mitchel Field on Hempstead Plains on Long Island in New York. This time written just to his father. He was closer to leaving for overseas, yet it turned out he still did not know where he would finally be stationed:

Dear Dad,

I got your letter yesterday and I felt I better write today, as I think we are leaving here Saturday or Sunday. We get our own plane and will fly to New York, then back down to Florida, South America and Africa. I don't know if I'm going to England or Italy. There seems to be a good chance of going to Italy. I'd like that better.

Italy is not foggy and damp and cloudy as England. Lots of sunshine, but I guess down there the air crews have to do a lot of their own maintenance on the ships besides flying it. In England they have a pretty good ground maintenance force. Either way I'm happy, want to get going, the waiting has been long enough.

Flying over will be quite an experience, especially the route we take. I hope my camera you sent gets here before I leave. I didn't realize that we'd go all of a sudden when I had you mail it to Langley.

It's good that the jacket I sent home fits you so well. Too bad the first one didn't, as black would have been real sharp with your uniform. I'll put one over on Ma by sending this to you at Fort Lincoln. Tell everyone 'hello.'

Love, Ernie

On January 20th, 1944 Ernest received his orders. Later that day he wrote a letter to his family, "I'm leaving for overseas in a couple hours and will enclose all the money I have on me. $200 in money orders. Use it as you wish. I’m heading to England, guess I better bring my warm clothes.” With that understated note to his parents, Ernest acknowledged that he was set to go overseas, where a war was raging.

In his letters home, Ernest expressed enthusiasm about playing a part in what the 8th Army Air Corps was trying to accomplish with daylight bombing. Of course flying daylight missions in the skies over occupied Europe was exceedingly treacherous. Casting any serious apprehensions aside, his vision was looking forward to flying.

Browsing through my father’s Air Corps archives just days after he passed, I began recalling the countless talks about his wartime experiences. They reel forever in my memory. His Army trunk was chock full, plus his closet shelves stacked with neatly marked boxes of photographs, letters, cards and documents. His closet held his Air Corps uniform, two A-2 leather jackets, the one I grew up wearing on my first dozen or so birthdays; the renown 'Lili of the Lamplight' painted jacket. It was stunning what he had kept and at first, overwhelming. As the days and weeks passed, I was becoming very familiar with a 19-22 year old father that I never knew.

Finally On The Way – The First Attempt

On January 23rd, 1944, the ten man crew took off in their B-17 from Langley. They flew up the east coast to New York City and landed at Roosevelt Airfield on Long Island. They billeted nearby for the evening at Mitchel Field.

A day later they embarked from Roosevelt, taking the Northern Atlantic route, and the eventual intention of making it to Scotland. In my Father Lt. Ernest Anders Erickson's thinking they were following the same path Charles Lindbergh took to Europe on his transatlantic flight of May 20, 1927. My father noted that fact often when he talked of that first attempted journey to England.

The Northern Atlantic route was a treacherous situation for many of the crews attempting the same passage. A considerable number of crews came across difficult navigation issues and horrendous weather. Many ships just did not complete the journey, either lost at sea or forced landings wherever they could possibly ditch the plane. Some crews, if they were lucky to find land, ditched in Greenland or Iceland. For the unfortunate crews that ended up in sudden sea landings in the dark cold Atlantic, survival was dismal.

My father's final stop in the United States was to be at the Presque Isle Army Air Force Airfield in Aroostock County in Northern Maine. Presgue was set up for ships heading to England via the Northern route. Aroostook was named for an Indian word meaning 'beautiful river.' It was activated as an Army Air Corps field in September of 1941, where the Air Transport Command was set up assisting the ferrying of bombers across the Atlantic to the battlefront.

The crew's flight was textbook flying, filled with hours of exciting sights and memories, but as they landed in a dense fog, while taxiing on the tarmac, another B-17 maneuvered into their path, causing a collision. No one was hurt, but both ships were badly damaged and would need extensive repairs. The crew was ordered to return by Air Transport to New York City where they awaited instructions in acquiring another B-17.

On February 3rd, 1944 my father wrote a letter to his family. He was so close to the war, yet obstacles were getting in the way of him actually getting overseas. He wrote:

Dear Dad, Mom & Dinny,

Well, here I am back in New York City again. The last time I wrote to you I was at Mitchel Field and expected to take off anytime on the first leg of my trip overseas. I took off a couple of hours after I wrote to you. Got as far as Northern Maine. Our ship and another one had a taxi accident and the repairs will take several weeks.

We were sent back to New York and now expect to go to England by Air Transport Command or hopefully we will get another ship. It's all up in the air as I write this now. We can stay anywhere we want to just so we phone in and report personally once a day to the Transport Headquarters.

This hotel (The Commodore) is located very near Grand Central Station and it's on 42nd Street. Lots of action going on here. It sure was a tough break about the accident. We don't have our own plane now, so don't know what the deal is for us after we get overseas. Of course we may get another plane that's been flown over by Air Transport Command or we may get another one on this side (hope so!)

It sure is a good deal though to be in New York City. Did you get the $200. I sent I haven't got any mail since I left Langley. The day I left I received a note from the mail-room that I had a package, the camera I hoped, and went over to get it , but the fellow that has the key for the insured mail room wasn't there. I went back two or three more times, but still no luck. I imagine it was the camera. I may be able to get it forwarded here to New York. It'll more than likely be a wreck when I do get it. Tell everyone hello. Will write again in a day or so.

Love, Ernie

My father's B-17 crew was finally assembled in October of 1943 at the training base in Dalhardt, Texas. They

moved onto Langley Field in Virginia for further training in the use of the H2-X radar device, which would be

onboard their B-17 when they headed over the North Atlantic.

Here are the names and positions of the original crew that left the States for England in February of 1944.

Lt. Ernest Anders Erickson – Pilot * Lt. Thomas M. Bachuzewski - Pilot

Lt. Haskel N. Niman Navigator * Lt. Earl E. Pirtle – Bombardier

Staff Sgt. Marion F. Pratt - Ball Turret Gunner * Staff Sgt. Jackson C. Earle - Right Waist Gunner

Staff Sgt. Arthur J. Fitzpatrick - Top Turret/Engineer * Staff Sgt. Conrad W. Roellchen - Tail Gunner

Staff Sgt. Gerald B. Engler - Left Waist Gunner * Staff Sgt. Edward R. Sambor - Radio operator

Most listed above would fly 12 different B-17s during the course of their 35 combat missions.

The ship that they most identified with and flew near 20 missions aboard was the 'Lili of the Lamplight.'

Here is a list of the twelve B-17s flown between March and September 1944 out of Horham Airfield.

Lili of the Lamplight (44-6085) * Taint A Bird II (42-30342) * Fireball Red (42-31876) * Able Mable (42-31920)

Mirandy (42-31992) * Gen'ril Oop & Lili Brat (42-31993) * Ten Aces (42-38178)

Smilin' Sandy Sanchez (42-97290) * Paisano (42-102450) * Stand By / Goin' My Way (42-107204)

The Doodle Bug / What’s Cookin? (42-107047) * To Hell Or Glory (42-38123)

Off To England One More Time and Marlene Dietrich

The two Pilots, Lt. Erickson, my father and Lt. Thomas M. Bachuzewski and the Navigator Lt. Haskel N. Niman did receive their ship and were assigned a new B-17, a Command Ship equipped with the H2-X radar device. Their familiarity with the system enabled them to get the 'Flying Fortress' far quicker than expected.

On February 5th, their second attempt to make the crossing of the North Atlantic, they were aboard a sparkling silver Flying Fortress, the three man crew left Langley early that cold Winter morning. They began the first of a half dozen flights that would inevitably get them to England. They looked forward to the elaborate hop, skip and jump journey over the North Atlantic. That traversing odyssey would take five days with multiple stop-overs. This time, as luck would go, following the same Northern Atlantic route, the trip would be successful. My father was duly impressed with his first long flight experience, the breathtaking horizons and frequent low altitude flying over the Atlantic was forever memorable.

This was my father's first time journeying outside the United States, his thoughts of flying like Lindbergh across a vast ocean with the thrill of flight always was at his attention. The crew was full of excitement with their destination, England in each of their thoughts. The crew headed for Roosevelt Field in New York then onto the Airfield at Presque Isle in Aroostock County in Northern Maine. They left the Maine the next day, landing a few hours later at Gander Airfield in Newfoundland. The men awaited on the farthest tip of Quebec, Canada for their next leg of their journey. The crew would soon be leaving North America behind and heading over the Labrador Sea, as my father would say, “It was the beginning of the most exciting adventure of my life."

Finally On The Way - The Crossing of the North Atlantic

The next day the Flying Fortress was off for Narsarsuaq Air Base in Greenland. The Three Airmen stayed long enough to look around the Air Base and talk to other crews, getting a true feeling of what they were undertaking. Later that day of February 8th, they took off for Reykjavik, Iceland where they awaited final instructions for their flight to Scotland, the final leg to the United Kingdom, where they would be soon, hopefully, assigned a Bomb Group and where they would be stationed in England. As the flight reached the United Kingdom, everyone on board acknowledged that soon they would be applying all they had learned in training. With thoughts of home and all that was occurring presently in their minds, brought the men to quiet contemplation.

The men arrived in Reykjavik at the right time, Lt. Erickson, Lt. Thomas M. Bachuzewski and Lt. Haskel N. Niman were present for a Marlene Dietrich performance. Dietrich made two overseas USO tours during the war. Anyone who was fortunate to see her, lit up with her singing and stories. "I'm here, I'm here," Dietrich would say, and then run down the gangway in her uniform, carrying her case. She would then produce a pair of evening shoes and a dress, and pretend that she was about to change right there on stage. The boys began to hoot and holler. Then two soldiers with grins on their faces escorted Marlene off into the wings. For the sexy comical charade, the whistles of encouragement from the audience continued to be heard. She returned dressed and ready for the show, joked and talked to the men, and sang her songs. 'No Love No Nothing, 'Lazy Afternoon,' and 'The Boys in the Backroom' were staples at her shows, as was the song that would eventually become identified with her forever, 'Lilli Marlene.' One of many one-of-a-kind unforgettable moments for my father he would say. Marlene Dietrich and her song, 'Lilli Marlene' were on his mind when he and the crew named their B-17 months later, the 'Lili of the Lamplight.'

On February 10th, 1944, Lt. Erickson and crew took off from Reykjavik for the final haul over the North Atlantic Ocean from Iceland to their first stop, Scotland. The ocean vistas spanning the horizon in every direction as they flew low over the North Sea en-route to England were breathtaking. Lt. Ernest Erickson was transfixed as he thought about the challenges that lay ahead. Over the course of 1944, he would send 100s of letters and cards to his family and friends back home. He would often include the many photographs he took

with the camera he finally received. Some of the letters he wrote during his combat flying read like fiction, others just simple requests to his mother to send chocolate, comic books, candy, pretzels and film for his camera. In these moments, I see my father as the adolescent, still clinging to what he was familiar with, yet in regards of his accomplishments of that time, a true anachronism. At this point he was twenty one years old and would soon be receiving a serious dose of the Luftwaffe and the dreaded black flowers (flak) that seemingly floated in the air.

95th Bomb Group * Horham Airfield * England

On February 11th, Lt. Erickson, Lt. Bachuzewski and Lt. Niman touched down in Prestwick, Scotland. They had made it with no difficulties and were excited to be on a Royal Air Force airfield. They awaited orders where they would be serving their combat flying tour of duty. The seven man crew, Bombardier Lt. Earl E. Pirtle, Top Turret/Engineer Staff Sgt. Arthur J. Fitzpatrick, Left Waist Gunner Staff Sgt. Gerald B. Engler, Right Waist Gunner Staff Sgt. Jackson C. Earle, Radio operator Staff Sgt. Edward R. Sambor, Ball Turret Gunner Staff Sgt. Marion F. Pratt and Tail Gunner Staff Sgt. Conrad W. Roellchen who had come over on the Queen Mary from New York had arrived on the 6th of February and had been awaiting the arrival of their new Flying Fortress. On February 15th the ten man crew took off from Prestwick and later touched down in England in South Ayrshire on the west coast of Scotland. This is the same airfield that in 1960 Elvis Presley, for the first time in England, arrived when his Army transport stopped en route from Germany.

On February 19th, the crew was off to the Royal Air Force Station at Stoney Cross. They would billet at Stoney Cross till mid-late February and then would be off to Royal Air Force at Alconbury. Leaving Alconbury the crew would fly off to their permanent assignment in England at Station 119 in East Anglia at Horham Airfield. East Anglia comprises the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. Ironically, East Anglia is derived from the Anglo Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a tribe whose name originated in Anglia in Northern Germany.

334th Squadron

Having been assigned to the 334th Squadron of the 95th Bomb Group, Lt. Ernest Erickson and crew arrived on February 28th, 1944 at the airfield in Horham, England. The airfield was originally used by the Royal Air Force, but by 1943 Horham was transferred to the 8th Air Corps. Lt. Ernest Erickson and crew were pleased they would be assigned to a permanent base. They would soon feel comfortable with their new surroundings. The field was located next to the village of Horham and four miles southeast of the village of Eye in Suffolk. The large airfield straddled the parishes of Denham, Redlingfield and Hoxnethey. Two hangars had been erected on the south side of the airfield and painted in black and dark earth camouflage. The airfield’s headquarters, miscellaneous buildings and housing huts, spread to the west of the airfield into Denham. Horham was given the designation of Station 119 by the 8th Army Air Corps.

My father and the crew were billeted on base, though separated into officers and non-com barracks, and each found their comfort in one way or another. The frigid gray-skied English weather was familiar to my father. He commented on the sky being rarely blue and sunny, but when the sun shone, he was one of the first outside to find a spot to lay in the sun.

Days rolled by and the crew flew local practice runs, concentrating on take-off, landing and formation flying, while looking forward to when they would be on a mission over mainland Europe. Orders were issued that seriously disappointed the crew, but a common occurrence for rookie crews showing up in England. Before they could fly their first mission in their ship, the soon to be Bomber Boys were notified their airplane was to be transferred to another bomb group. My father and crew, resembling gypsies during their first months at Horham, were once again without a ship. Before their tour of duty came to an end, they would fly in a dozen different ships, completing the maximum of missions over Europe.

The Crew

The ten-man crew of a B-17 Flying Fortress consisted of two pilots, navigator, bombardier / nose gunner, flight engineer / top turret gunner, radio operator, two waist gunners, ball turret gunner and the tail gunner. The 17's carried 8,000 pound (3,600 kg) bombs on short runs, and 4,500 pound (2,000 kg) bombs on long range missions. With a total load capacity of 17,600 pounds (7,800 kg) the B-17 was a formidable weapon. Thousands of these bombers were flown by the Eighth Air Force between 1943 and 1945, in a grueling campaign that eventually devastated German military and industrial infrastructure. Between late March 27th and August 26th, 1944, my father and crew flew 35 missions over Europe.

Daylight bombing was an especially deadly enterprise which took an enormous toll on the airmen of the 8th Air Force. Losses of anywhere from twenty to fifty bombers during a single mission were not uncommon. With the ten- man crews aboard each plane, two hundred to five hundred men could be lost on any given day. The odds of survival were especially grim in 1943 and into mid 1944. During this deadly period, the odds that a B-17 crew member would survive the war were less than 50/50.

On some missions, more than one out of every ten planes were lost. When my father arrived at Horham, he was told that crewmen would be asked to fly no more than twenty-five missions. Facing the reality of enormous losses and subsequent depletion of trained airmen, the Air Force disregarded that promise. In his letter of April 9, 1944 my father mentioned that the number of missions he would be flying had increased to thirty. By the time he reached his thirtieth mission, the number had been raised to thirty-five. Those last five missions would be the most interesting flying my father would ever experience while stationed in England.

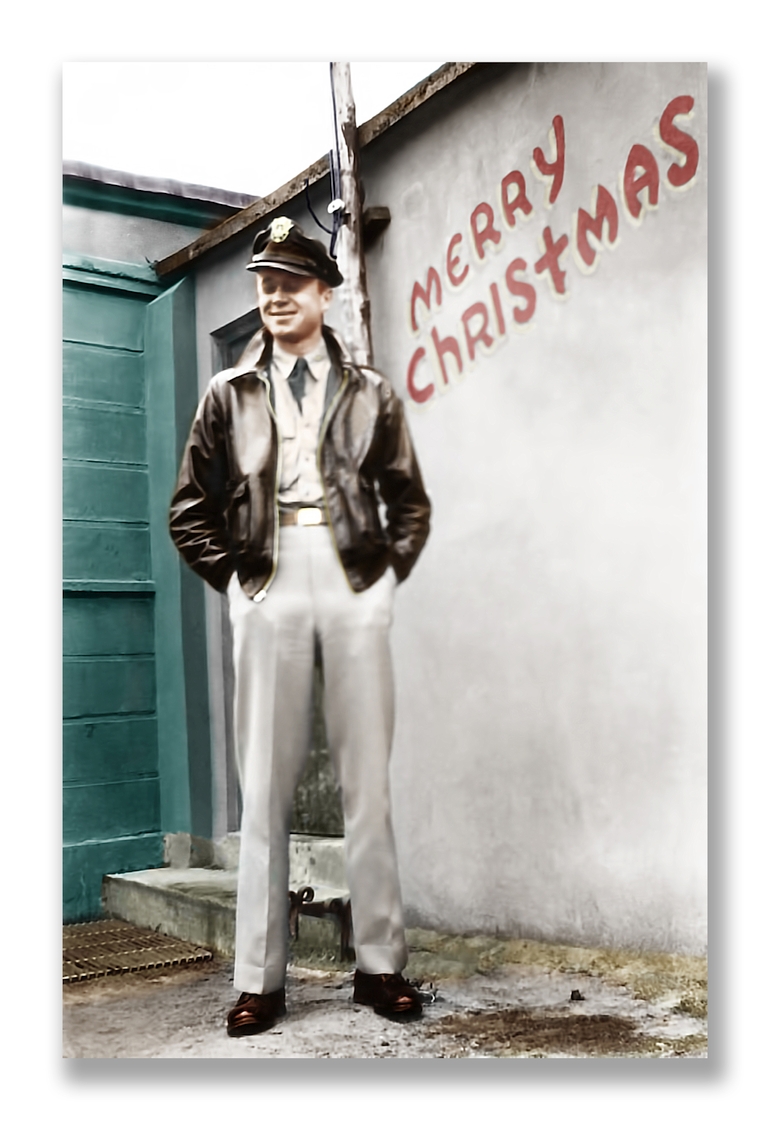

First Photograph:

Merry Christmas Lt. Erickson

My father standing with a big grin on his face in front of the Red Feather Club at Horham Airfield (Station 119) where he was stationed with the 95th Bomb Group in England in February of 1944. He'd been looking keenly forward to getting to England and his combat flight assignment, even though he missed Christmas 1943, he was ready for Combat Flying. He flew B-17 training flights through February and March and completed his first mission March 27th, abroad 'Mirandy' (42-31992) over a target at Cazaux, France.He completed his 35th mission with 334th Squadron on August 26th, 1944 aboard 'Stand By/Goin' My Way' (42-107204) over a target in Brest, France.

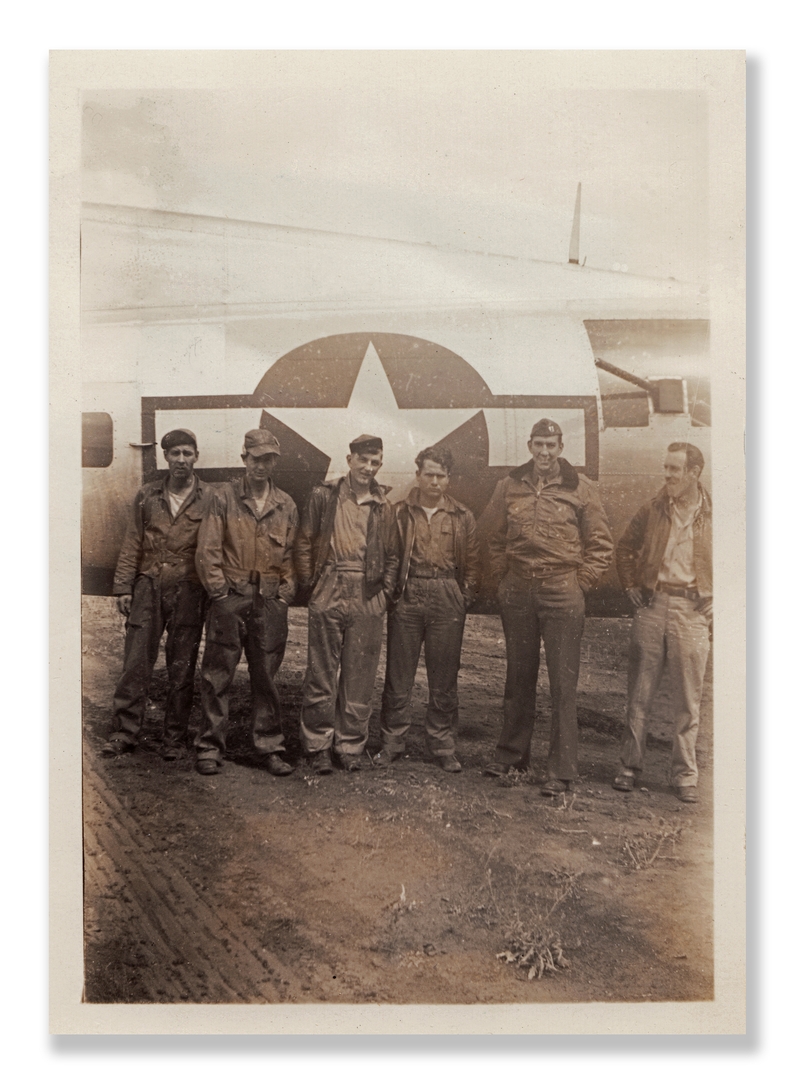

Second Photograph:

A photograph of the Crew taken in early 1944 at Horham Airfield, England.

Third Photograph:

A photograph of the Crew taken in mid 1944 at Horham Airfield, England.

Left to right:

Lt. Haskel N. Niman - Navigator

Staff Sgt. Gerald B. Engler - Left Waist Gunner

Staff Sgt. Edward R. Sambor - Radio operator

Staff Sgt. Marion F. Pratt - Ball Turret Gunner

Lt. Thomas M. Bachuzewski - Pilot

Staff Sgt. Arthur J. Fitzpatrick - Top Turret/Engineer